Three phenomena on the labor market have emerged and persist:

- inactivity – significant number of discouraged persons not looking for work,

- long-term unemployment, with increasingly longer periods of unemployment;

- and the insecurity trap, which means that the majority of people who have insecure jobs or informal jobs find it very difficult to move into stable employment.

The most vulnerable groups are in general also marginally attached to the labor market because of significant employment obstacles. Understanding these barriers is essential for designing Policies to sustain disadvantaged workers to overcome them.

The main concepts, terms and expressions used in discussing these aspects are listed and explained below.

The economically inactive – disadvantaged workers

Technological advances and labor market

Policies to sustain disadvantaged workers

Active labor market (ALM) measures

Active labor market (ALM) measures for the vulnerable, labor market excluded

Private employment services – PrES

Work integration social enterprises

The economically inactive – disadvantaged workers

The International Labor Organization (ILO)’s concept of inactive person (neither employed nor unemployed) includes people who are mainly in education or training (on average in EU 35% of the inactive), retired (14%) or suffering from illness or disability (16%), those who are looking after children or incapacitated adults, or have other family and caring responsibilities (17%), as well as those who are discouraged and think no work is available. Overall, the discouraged sub-group is quite small, only representing 4% of all inactive persons. However, in some countries, discouraged workers remain relatively significant, with a share of more than 10% of all inactive persons.

The economically inactive have a varying degree of attachment to the labor market meaning they also have a varying activation potential. The inactive would in fact to some degree like to work even though they are not actively seeking work. ‘Willingness to work’ is prevalent among a considerable section of the inactive population. Experts consider using ‘willingness to work’ as a proxy for activation potential – and estimate that about one in five of the inactive population are in principle interested in working.

Individual activation barriers

Besides country-specific institutional barriers, there are a set of common obstacles facing the inactive population at the individual level. These common activation barriers include:

- Low employability due to low educational attainment and/or lack of work experience;

- Health problems or disability;

- High level of social exclusion.

These barriers often interact. People with health problems and disabilities are among the main groups that face multiple barriers in finding employment. Illness or disability is the second most important reason for the inactivity of older workers aged 55-64. Among inactive people with low educational attainment, it is particularly common to have no work experience or to have childcare responsibilities. Many inactive people who provide elderly care are also frequently limited by chronic health problems or disability. Hence, disadvantaged or vulnerable groups (individuals with disabilities and poor health, with immigrant background, ethnic minorities and individuals with low formal education) are overrepresented among the inactive population.

Most inactive groups are not registered with the Public Employment Services (PES) and thus not known to them, the outreach to inactive and difficult-to-reach groups depends on close partnerships with a variety of public and private stakeholders. Given that many economically inactive people are not yet able or ready to (re-)enter the labor market, support from other institutions is clearly required. Therefore, communication and cooperation is a crucial feature of the actions undertaken by the PES vis-a-vis different target groups, including NGOs.

Source: Activation of the Inactive: PES initiative to support the activation of inactive groups Thematic Paper – Directorate-General for Employment Social Affairs and Inclusion, European Network of Public Employment Services, 2020

Long term unemployed

Long-term unemployment is typically defined as anyone who has been unemployed for twelve months or more. Long-term unemployment can be indicative of a lack of access to opportunities for some. This lack of opportunities can discourage job seekers, who may choose to leave the labor force altogether, thereby not being further recorded in the unemployment numbers.

Countries differ widely in the share of long-term unemployed, ranging from near zero to almost ¾ of all unemployed. Almost half of the unemployed people are still long-term unemployed, that is, unemployed for more than 12 months. Long-term unemployment has implications for society as a whole, with dire social consequences for the persons concerned and a negative impact on growth and public finances, being one of the causes of persistent poverty.

Long Term Unemployment Factors

Several factors contribute to high long-term unemployment.

Workers – Human capital depreciation. Individuals may lose some of their human capital during unemployment and become less attractive to employers. For instance, a factory worker who has been without work for over a year may have lost basic skills such as the ability to work in a team and show up to work on time.

Firms – Changing technology and consumer tastes might mean that some workers’ skills are no longer demanded by employers to the same extent. Re-training for different jobs may be lengthy, difficult, and costly. For example, a coal miner who has lost his job due to falling demand for coal may find it costly to retrain as a wind turbine technician.

Macroeconomy & labor market institutions – Some of these features may be exacerbated by labor market institutions.

Informal workers

The informal sector describes small-scale firms and activities that are unincorporated and unregistered for tax, regulatory, and other legal purposes. Informal employment includes self-employment and wage employment that is not protected by secure contracts or other legal and regulatory systems.

The definition and causes vary across countries. For example, some workers and firms exit the formal sector, discouraged by its high tax and regulatory burdens; some have no employment options in the formal sector, and thus rely on informal employment; and others choose informal activity for its flexibility and independence.

These varied reasons for participating in the informal economy mean that informal workers may range from agricultural day laborers to self-employed lawyers with a few employees. The informal sector does not cover illicit activities such as illegal drug trafficking and smuggling.

The informal sector employs individuals with lower skills and less education, and those who are typically either younger or older than workers in the formal sector. It is also more prevalent among women and in rural areas where there are fewer alternatives in the formal sector and where the agricultural sector dominates.

Globally, higher levels of education are correlated with lower levels of informality. People who have completed secondary and tertiary education are less likely to be in informal employment compared to workers who have either no education or completed primary education, although there are wide variations across regions. Further, people living in rural areas are almost twice as likely to be in informal employment as those in urban areas. Agriculture is the sector with the highest level of informal employment – estimated at more than 90 percent. Informality is higher among young and old people. Worldwide, three out of four young and old people are in informal employment.

Source: Inclusive Growth: Labor, Gender, and Technology IMF Capacity Building Course notes 2021

Technological advances and labor market

Technological advances can raise overall productivity and income—and they often are disruptive. They can lead to structural change, creating new jobs and sectors while displacing and changing others, with major repercussions for some parts of the population.

Labor-saving technology could have profound negative implications for equality in the labor market. If robots are almost perfect substitutes for human labor, the good news is that output per person rises. The bad news is that inequality worsens, for several reasons.

- First, robots increase the supply of total effective (workers plus robots) labor, which drives down wages in a market-driven economy.

- Second, because it is now profitable to invest in robots, there is a shift away from investment in traditional capital, such as buildings and conventional machinery. This further lowers the demand for those who work with that traditional capital.

- In the long run, the share of capital owners and their consumption spending grows. With falling wages and rising capital stocks, (human) labor becomes a smaller and smaller part of the economy.

Policy response

Technological progress will raise productivity and incomes, but large fractions of society may be left behind. There’s great uncertainty about the pace and magnitude of the coming disruption. A policy response will therefore be needed to mitigate this impact – policies should establish springboards and safety nets through investments in education and redistributive tax, spending, and social policies.

- Investments in education will provide a springboard for a new generation of workers by equipping them with the skills to cope with technological advances including AI. The quality and adaptability of education will make all the difference in preparing workers for change. Investments in human capital take time to yield benefits, so early action is needed.

- Social safety nets will be required to protect groups hurt by technological progress.

- Redistribution policies should be designed to facilitate mobility and adjustment while minimizing adverse effects. For example, many commentators have advocated a universal basic income, or UBI, whereby all individuals are paid a benefit independent of the employment status and with the level of payments geared above the poverty line. While such programs would imply fiscal costs and with it distortionary taxes, those could be contained if a UBI replaced other social programs.

- Expenditure policies that increase the demand for unskilled labor may serve double duty. They raise demand for unskilled labor and push up unskilled wages, thereby decreasing overall inequality. One example would be investing in digital infrastructure in poorer areas to allow all citizens to access the internet. And other infrastructure investments include public transportation that connects lower income workers with jobs.

Investments in education, infrastructure, and safety nets should be funded by fiscal reforms. These reforms could include scrapping harmful tax exemptions and subsidies, especially energy subsidies that often benefit high income earners, and improvements in tax policies and tax administration.

More progressive taxes on capital and rent could be introduced including on monopoly rents of digital giants that wouldn’t introduce major distortions. Property taxes, especially on real estate, could also be raised where they are currently low, improving progressivity while being very efficient, as they are levied on an immobile base.

Economic policies

With increasing automation in manufacturing, developing countries need to move beyond export-led manufacturing to other sectors, including agriculture and services.

In agriculture, AI offers the potential for large productivity increases based on algorithms that, for example, help farmers optimize decisions to increase their yield.

In services, investment could be encouraged in healthcare and education, which are labor intensive and important for economic development.

In summary, to reap the considerable benefits of technology, early policy action in a range of areas will be needed to mitigate the short-run adjustment costs and to maximize the benefits of technology for all.

Policies to sustain disadvantaged workers

Polices designed to sustain disadvantaged workers can be classified in four main groups:

1. Regulatory policies, which consist of the adoption of quota systems that oblige all or some enterprises to hire a minimum percentage of disadvantaged workers.

2. Compensation policies, which are designed to encourage enterprises to employ disadvantaged workers by compensating them for the lower productivity of the disadvantaged workers employed or for the hiring and training costs involved.

- Incentives for recruitment of disadvantaged persons

- Funding for training & guidance before recruitment

- Funding for the adjustment of workplace to better suit the needs of disadvantaged workers

- Financial coverage of paid internships for disadvantaged worker

3. Substitutive policies, which are aimed at creating a “substitutive labor market” that is an out-of-the market demand for disadvantaged workers specifically – sheltered employment operated via public companies and/or public/private sheltered workshops, as for private enterprises

4. Supported employment, which consists of a mix of policies that intervene directly with dedicated tutors to support the selection and training costs of enterprises integrating disadvantaged persons to work – individual placements in conventional enterprises, individualized training interventions, mobile work crews

Source: EURICSE working document for BWISE project – ENSIE RISE 2021

Active labor market (ALM) measures

The purpose of ALMPs is to enhance the employability of job seekers, connect workers and jobs, and promote job creation. ALMPs typically fall into the four broad categories as shown in the table below:

ALMPs are costly and would need to be financed through increased taxation. If this taxation were imposed on labor it may create disincentives to work and could make the overall net benefits of the programs ambiguous.

There is evidence suggesting that some programs are more effective than others: for example, assistance with job search works generally well, as does training and well-designed wage subsidy schemes. However, public job creation (e.g., public works programs) is less effective in helping workers over the long run.

The consensus is that for all programs, the design, targeting, and implementation are paramount in ensuring its effectiveness. Well-targeted activation measures are those tailored to the needs of the beneficiaries.

Active labor market (ALM) measures for the vulnerable, labor market excluded

The most vulnerable groups are in general also marginally attached to the labor market because of significant employment obstacles. The lives and circumstances of jobless people, or those with intermittent, low-paid or unstable employment, are rarely simple. They are often confronted with complex and inter-related employment barriers, such as skills deficiencies, health problems, financial disincentives or care responsibilities. Understanding these barriers is essential for designing policy interventions to overcome them, but systematic and good-quality information on the nature and extents of employment obstacles is currently missing.

Many of these people face multiple employment obstacles, such as a combination of

- low skills,

- care obligations,

- health limitations,

- addictions

- geographic mobility challenges

They could though find employment if given appropriate active labor market policy (ALMP) support coordinated with other services. Other services (such as health and social services to combat addictions or health limitations) need to be at times provided even before effective provision of ALMPs becomes possible, and need to continue going hand-in-hand throughout the labor market integration process.

As the most vulnerable groups face often very specific or even multiple obstacles, it is important to provide them with individualized support, and at times even tailor-made support, to meet their complex needs.

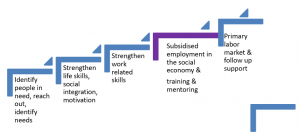

From the PES side, this requires a combination of different ALMPs, such as training to increase digital skills to improve employability, followed by job-search assistance, and potentially employment subsidies. In addition, the inclusion pathway often requires a step-by-step approach which relies on the co-operation between institutions, as other types of services (social, health, education, childcare, housing and beyond) as well as social protection measures and benefits might be needed before as well as during ALMP provision to tackle social integration obstacles more generally (Figure 1).

Key features of successful employment programs for the most vulnerable groups

Private employment services – PrES

Ministries and PES cooperate with a number of different types of providers to implement ALMPs, including companies specializing in employment services, training providers, temporary work agencies and not-for-profit organizations providing ALMPs.

Involving PrES in ALMP implementation can facilitate changes in delivery models in some cases and provide an additional tool to increase system agility. For example, in case a well-developed market for PrES exists, depending on the procurement laws and civil service regulation, it might be quicker to increase the provision of employment services by extending the use of PrES than increasing the staff numbers in PES offices (or indeed both channels can be used simultaneously to meet fast changes in needs for ALMPs).

On the other hand, in case employment services are contracted out to PrES, the public sector partner (ministry or PES) has somewhat less control over the service provision and fewer tools to initiate changes in case labor market needs change. For example, it might be difficult to change the contractual terms in response to sudden changes in needs, such as an outbreak of a global pandemic. The continuation of service provision may then largely depend on providers’ willingness to co-operate and the legal framework to amend existing contracts.

Source: Institutional set-up of active labor market policy provision in OECD and EU countries: Organizational set-up, regulation and capacity, Anne Lauringson, Marius Lüske – OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 262 -2021

Work integration social enterprises

For some of the most vulnerable groups, one step on the pathway to labor market integration can be subsidized employment or some other type of support involving the social economy. Innovative approaches involving the social economy can bridge the transition to the primary labor market. [1]The effectiveness of these programs is dependent on their exact design. To be effective, subsidized employment in the social economy is provided simultaneously with training and mentoring with the aim of integration of vulnerable workers into the primary labor market in the longer run.

The failure of most labor policies – including combined policy measures through supported employment – have opened the way to new initiatives, including the emergence of autonomous organizations explicitly created for training and employing disadvantaged workers directly, either in stable or temporary ways: Work Integration Social Enterprises (WISEs).

WISEs can be defined by three identifying pillars: (1) they are enterprises whose main objective is the social and professional integration of disadvantaged people, (2) they are at the core of the economic system and (3) present a strong pedagogical dimension. WISEs integrate disadvantaged workers into work and society through productive activity and pay disadvantaged employees a pay that is equal or at least comparable to that of other workers. WISEs are engaged in a plurality of income generating activities. Resources obtained through market exchanges can either derive from contracts established – in more or less competitive forms – with public authorities, for instance for the maintenance of public green areas and for cleaning public offices, or from business-to-business exchanges.

To empower and take stock of the skills of disadvantaged workers, WISEs have developed a number of alternative strategies: i) creation of transitional occupations that provide work experience and on-the-job training with a view to supporting the integration of the target group in the open labor market. Training periods before recruitment by the same WISE or by other employers – only partially paid by the same WISE or by public entities – are in this case possible; ii) creation of permanent jobs that are sustainable alternatives for workers disadvantaged in the open labor market.

WISEs include two main typologies of organizations that comply with the above mentioned definition:

- enterprises with a longstanding tradition in employing people with disabilities that have existed for 50+ years in some EU MSs (e.g., companies for people with disabilities);

- enterprises that have emerged (often bottom-up) to facilitate the work integration of people excluded from the labor market.

[1] Building inclusive labor markets: active labor market policies for the most vulnerable groups © OECD 2021

European Union policies and actions for the integration of the long-term unemployed in the labor market

Addressing long-term unemployment is a key employment challenge of the European Commission’s jobs and growth strategy.

In February 2016 the Council adopted the a Recommendation on the integration of the long-term unemployed in the labor market.

In April 2019 the Commission adopted the Report on the implementation of the Council recommendation taking stock of progress made.

“The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the National Agency and Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein”.